Scene 11: YOU WANNA BE A PRODUCER

Copyright 2012 Neill Fleeman

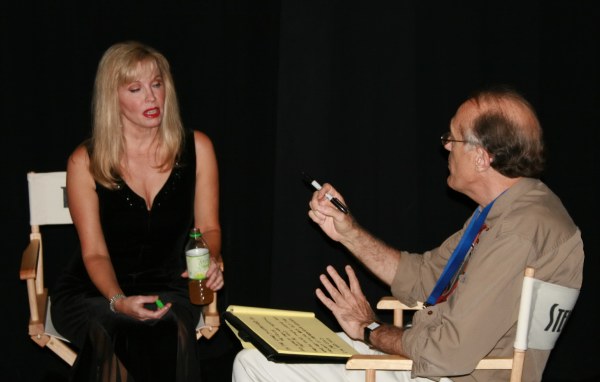

Elizabeth Williams Grayson and your author work out the details of a scene in The Third Act

In Mel Brooks' The Producers, accountant Leo Bloom sings “I wanna be a producer - and drive the chorus girls insane!”

That's all well and good, an admirable, perhaps even noble sentiment. And aside from going to jail things work out pretty well for Leo; he winds up with Uma Thurman. But what about the rest of us?

You may remember that a few years ago, during a slump in local film production due to the Screen Writers Guild strike, the local legislature's foot dragging on tax incentives for film production, melting polar ice caps and a planetary alignment with Neptune and Pluto, the merry little band of local thespians known as the Yadkin Valley Railroad Little Theater Players, Extras, and Pinochle Society thought it might be interesting to try to produce our own film. The logic in this, so far as it went, was that I had written a bunch of stuff before, and written and directed industrial films, and with the digital tools now available it shouldn't be that hard.

Right.

After a few false starts I dug around in the trunk and came up with an old story I dusted off and turned into a feature length screenplay called The Third Act. A major studio feature film now costs, on average, $100 million to produce so we scaled back our thinking a little to a 52 minute short feature and got to work.

That was three years ago. As this is written we are now about ten days away from being ready to preview the film and are starting to think we might actually live through the undertaking.

So you wanna be a producer? Don't say I didn't warn you.

WHAT'S YOUR STORY?

In Robert Altman's great Hollywood backstab The Player, movie studio honcho Griffin Mill (Tim Robbins) is telling a writer's girlfriend (Greta Scacchi) why he didn't put her boyfriend's screenplay into production: “It lacked certain elements that we need to market a film successfully,” Mill says.

“What elements?” asks the girlfriend.

Mill: “Suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart, nudity, sex. Happy endings. Mainly happy endings.”

The girlfriend ponders this a minute. “What about reality?” she asks.

As readers of this very occasional chronicle may recall, your correspondent often waxes critical of most of the fare served up in today's multi-plexes. James Cameron's Avatar (or as we cynics called it, `Smurfs in Space') cost about $300 million to make and by the time the bean counters added promotion and marketing the total cost was about $600 million. But that's OK; it made zillions at the box office. The basic plot of `Avatar' was a tired old shaggy dog called The Squaw Man, a Jesse Lasky/Sam Goldfish/C.B. DeMille 1913 silent film based on a 1905 Broadway play that wasn't all that hot to begin with. But if you blow up enough stuff in 3D with computer-generated imagery no one notices your story has the weight of styrofoam. Films like Avatar or Harry Potter 14, or Spiderman 73, or Rocky 127 or Zombie Cheerleaders 3D have a lot of expensive flash and color making a donut around a hole where a plot should have been.

On the other end of the scale let's look at Leatherheads, the film that got me in this mess to begin with. Most of us who worked on the film really weren't clued into the over-all details of the plot but we knew in a general way that it would be literate because George Clooney doesn't do anything that isn't literate. And there's the rub: literacy in America is rapidly going the way of the dodo bird. If it hasn't been mentioned on “American Idol” in the last half hour it doesn't exist. The line about the Algonquin Round Table in `Leatherheads' nearly had me falling out of my seat but most of the 500 or so people who were in the theater didn't get the reference. And that is why `Leatherheads' is still several million dollars in the red even though it scored points in seven of the eight categories on the mythical Mr. Mill's list. (Alas, no nudity.)

So there in a nutshell, Mr. or Ms. Budding Producer, is your first big problem. If you're going to make a movie, you're going to have to tell a story, because that's what movies - theoretically at least - are about. And if you're going to tell a story, you're going to have to figure out how you're going to tell that story and who you're going to tell it to. Are you going to be Merchant-Ivory or Judd Apatow? To put it more simply, are you going to have comic book characters and flatulence jokes aimed at ten-year-old boys or take your chances with a more intellectual story for a more discerning audience?

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Consider this:

You're standing on the sidewalk outside a diner on Main Street in Small Town, USA. The smell of the stale grease from the deep fryers makes your stomach turn a couple of barrel-rolls despite the fact that it has been a long time since breakfast and you're starving. You look through the big picture window, between the foot-high red letters painted on the glass, into the dim interior where about two dozen people are having lunch at tables and a counter. You walk to the door, take a deep breath, and step inside. You're met by a wall of lunchtime chatter, the volume of which suddenly drops like someone clicked the knob on the radio. All eyes turn to you, the out-of- towner in the suit.

You glance around the interior. A big guy in a dirty apron walks over and looks you up and down, not exactly friendly. You don't look like his kind of clientele. “Ken I hep ya?” he asks.

OK. That's your cue. Your line is: “Hi. I'm producing a movie called `The Third Act' and we're looking for a diner location for a short scene. Is this anything you might be interested in?”

Got it? Good. Because in the next few months you're going to have to read that line a lot. You're going to have to read it to all kinds of people in all sorts of locations. And you're going to have to read it with great conviction because you really do need a diner. And a posh bed and breakfast. And a real working theater. And a down-at-heels apartment, an upscale restaurant, a Connecticut mansion, an English village street, a psychiatrist's office, and a dozen more locations. You need these locations because there's no budget to build sets on a soundstage. In fact, there's no sound stage. So all your locations are going to have to be real. But `real' is what your film's about, right?

FACING THE MUSIC

Janet Leigh has just stolen $40,000 from her employer and she's on the lam, headed to California to meet her boyfriend. She stops at a little motel off the beaten track figuring the police, when they look for her, will check the main roads first. She's tired. She gets in the shower, turns on the water and then there's a looming shadow, a glint of steel and -

SHRIEK!

SHRIEK!

SHRIEK!

SHRIEK!

Bernard Hermann and the orchestra open up with the violin passage that has become synonymous with Alfred Hitchcock's thriller Psycho.

Music is taken for granted in films and television. Themes identify the production and background music is used to set the mood. Some film makers - Woody Allen and Robert Altman to name two - are masters of musical selection to enhance their films; remember Allen's use of Gershwin's “Rhapsody in Blue” to introduce his Manhattan (1979)?

This brings us to an important point.

OK, let's say you have this nice little film called The Third Act and you've gotten to the point in pre-production that you are starting to consider the music. (That's right, you need to figure out the music BEFORE you start shooting the film.) You want to use Big Band music to create a sort of literate nostalgia motif. You settle on Benny Goodman Quintet playing “Moonglow”, Artie Shaw's “Begin the Beguine”, Tommy Dorsey's “Getting Sentimental Over You”, and a couple more. Perfect. Just what you wanted.

But you can't use them.

Why? Because songwriters have this strange idea that they should be paid for their work. The rights to use those five pieces of music in a motion picture will cost you a couple million dollars - even if your movie doesn't make a nickel. That's right, you've picked out a two million dollar soundtrack for your production numbers and you haven't even thought about the background music yet. That's why you don't hear great soundtracks much any more; filmmakers can no longer afford to spend that large a percentage of their budget on music.

So what's the alternative? There are a number of sources for non-royalty music made specifically to address this problem. Most of it is the sort of generic homogenized goo you hear dripping out of the ceiling in the grocery store. Or you can go the public domain route and find something so old that the copyright has expired. Or you can get somebody to write something for a one-time payment that sounds sorta-kinda like the song you really want to use but not so much like it that you'll wind up in court.

In our case the solution was staring me in the face the whole time and can serve as an example of how a bit of adversity can eventually lead you to not only solve your immediate problem but add unexpected value to your entire production.

The plot of our little epic turns on producer Steve Styne asking actor and playwright Tom Nichols to play the score of his parody musical `The Golddiggers of Forty-second Street' as a fundraiser for the regional theater where the pair, along with our female lead Katie Gordon, all worked twenty-four years before. Katie and Tom are thrown together again and the fireworks start.

As it happens, there really was a `Golddiggers' musical and songs for it existed. I knew this because I had written the `Golddiggers' book and most of the ersatz 1930's show tunes songs in 2003. I already owned the rights! So in the end, all I had to do was adjust the lyrics of three existing songs, write new lyrics to an existing tune, write four new songs from scratch, find a female vocalist, rehearse her and a jazz band, then go into a recording studio and lay down the tracks.

It was a snap. It only took two years.

A STAR IS FOUND

In the dim and distant days of Old Hollywood, some Producer, wanting to save a buck by not sending a crew to film on the actual location, told his Director “A rock is a rock, a tree is a tree; shoot it in Griffith Park.” That's fine unless, say, your location is supposed to be the South Pole or the dark side of the moon. Then those palm trees are going to look a little out of place. The same can be said of the actors in your film. Some people look the part; some don't. You wouldn't cast Charles Laughton in a part that called for a Cary Grant-type; to update the analogy, you wouldn't cast Jack Black in a part that called for a Brad Pitt-type, no matter how good an actor he was. As shallow as it may seem, looking the part is 90% of the deal.

Our chief problem in casting The Third Act was that the story takes place in Connecticut - but we were shooting it in North Carolina. When it comes to delivering dialogue, the two accents are totally incompatible. My Katie not only had to LOOK right, she had to SOUND right, too, and you don't get a lot of Connecticut accents in the available pool of Carolina actresses. For about a year I had my eye on women in the grocery store, drugstore, other film shoots, and walking down the sidewalk or in the mall, looking for someone who matched my idea of Katie. This was not nearly as exciting as it sounds.

We finally found an actress with considerable theater experience who passed the “look and sound” test. I asked her if she'd like to read the script. She responded eagerly and a few days later she emailed to say she loved the script. “Fabulous.” “Best thing I've read in years.” “I'm dying to do it.”

“Great! When can we have a meeting to discuss it?”

Two months later I got a lunch meeting. She again waxed poetic on the script's potential. Our shooting dates were creeping closer; when could we discuss wardrobe?

The wardrobe meeting took SEVEN MONTHS to set up. But on the day she didn't have time to discuss wardrobe. “Call me and we'll set something up.”

We began another three months of unreturned calls and emails. Our shooting dates came and went. Finally I gave up. I fired her. We put out a casting call for a white female, mid-40s, attractive, that could do a Northeastern accent. And what did we get?

Eighteen year old girls that spoke like they had never been out of the Carolinas in the lives. And a several guys. Yes, guys.

Well, that's Show Biz.

And then I got a submission from Broadway veteran Elizabeth Williams Grayson. She read the script and we scheduled a meeting a few days later.

Given my track record with actresses, when we were seated I asked her pointedly: “Why are you interested in this script?”

Elizabeth fixed her green eyes on me and delivered a line I had been waiting two years to hear: “This is my life,” she said. “This is me.”

And we had our Katie.

Now wasn't that easy?