Scene 8: THE PITCH

Copyright 2010 Neill Fleeman

Katie Gordon (Elizabeth Grayson) tempts fate in The Third Act

The Pitch

I sometimes wonder how Hollywood ever managed to produce a film in those dark days before the five dollar - or eight or ten dollar - cup of coffee. I mean, when Billy Wider pitched `Sunset Boulevard' to the suits at Paramount, Starbucks wasn't even a gleam in some film executive's bloodshot eye…

FADE IN: It's 5 PM on a February day in 2009 and I'm sitting in a coffee shop in Winston-Salem, NC. Sitting across the table from me is the young woman who directed me in a forgettable little epic called `Condos', produced for the University of North Carolina School of the Arts.

`Condos' was my first outing in what has become my “geezer” persona. It was also my first leading role and it nearly killed me. To say I was inadequate would be merciful; I was simply awful, bringing to mind Dorothy Parker's famous quip about Katharine Hepburn's performance in Jed Harris's dreadful 1933 production of `The Lake'. Dotty said: “Miss Hepburn's performance ran the gamut of emotion from A to B.” I wish I had done as well. My `Condos' character of Henry was not unlike Clint Eastwood's character in the recent `Gran Torino' and for me was so much against type that I never got close to getting it right. I've never even worked up the courage to watch it on DVD, despite rumors that it turned out pretty well.

`Condos' shot in late October 2008 and since then business in Filmland has gone from slow to slower. The economic downturn is one reason, the backwash of the 2008 writers' strike is another, contentious 2009 contract negotiations between the producers and the Screen Actors Guild a third. The state legislature's waffling over whether to extend tax incentives for film companies hasn't help either. But perhaps the biggest contributor in the decline in the local film business is that these days the preponderance of films are blow-`em-up-shoot-`em-up-everybody-flies-zombie-vampire-werewolf-special effects-cartoon pictures designed for the twelve year-old mentality. With that group as a target audience (“prime demographic” it's called) there isn't as much of a demand for the kind of films my little band of budding thespians is interested in: real people with real emotions doing real things in real locations. Of course there's more to it than the fact that most contemporary writers can't make a real story interesting; green screen backgrounds and CGI characters are easier to control, the weather is always good and the actors don't talk back, forget their lines, have run-ins with the paparazzi, fall off their motorcycles, or get their wardrobe dirty.

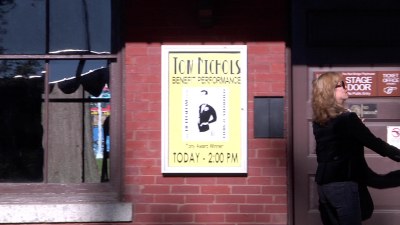

As you might imagine, this enforced hiatus has caused a significant amount of ennui among the sundry members of the Yadkin Valley Railroad Little Theater Players, Extras, and Pinochle Society. I mean, we're not getting any younger. And so several months ago, in the best Mickey Rooney-Judy Garland tradition of “My Dad's got a barn, let's put on a show!” and with the encouragement of the membership, I decided to take matters into my own hands. Our merry little band was a diversely talented group; if nobody was coming up with a film we could be in, we could very well do our own. Rummaging through my trunk of stories I came upon an eight thousand word piece I wrote in 2003 called `The Third Act' and in and around other projects I have spent the last year engaged in trying to turn the thing into a shoot-able screenplay.

“Audiences don't know anyone writes a picture,” says William Holden as down-and-out screenwriter Joe Gillis in Wilder's brilliant `Sunset Boulevard'. “They think the actors make it up as they go along.” Joe may have been off-base about a few things - he wound up floating face down in Gloria Swanson's swimming pool, after all - but he got that one right. The screenwriter has always been the low man on Filmland's creative totem pole - even though without a story the actors can't act, the directors can't direct, the producers can't produce, and the camera man can't roll film. On the other hand, try getting your screenplay on the screen without those other guys. Pretty tough.

So there I was on this particular dreary February afternoon, pitching my story to someone who might be able to get enough people interested in the project to get the thing in front of the cameras and in the course of a year or two put a bunch of actors and crew to work. After the usual preliminaries I took a deep breath and plunged right in with a synopsis:

“It's sort of a boy-loses-girl, boy-loses-girl, boy-loses-girl story,” I begin, tweaking the usual “boy-meets-girl” chestnut, trying to get a laugh. What it gets me is a smile about as thin as Turhan Bey's mustache. Undeterred, I press on: “Two characters, an actor and an actress, meet playing summer stock. There is considerable mutual interest but neither one tells the other how they feel and at the end of the summer they go their separate ways. A dozen or so years later, after career success and personal disaster, she decides it's time to live happily ever after. She pursues him and they have an affair that ends very badly. Another twelve years go by. They get thrown together again at the summer theater where they had first met. That's where we come in; twenty-four years of backstory told over the course of a night and a morning, without flashbacks, explosions, car chases, automatic weapons, or the living dead, distilled into about fifty minutes of screen time.” I tie a ribbon around it: “ `Same Time Next Year' meets `My Dinner with Andre' with a touch of `Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolfe?' ”

I looked over at my director. Her eyes are glazed over. I was two minutes into the pitch and already going down like the Hindenburg. Why? Everyone who had seen the preliminary script thought it had real possibilities. Suddenly it dawned on me what my problem was: I was talking about a story that played out over twenty-four years - and the director was only twenty years old. My characters were playing summer stock before she was born. The movies I referenced are ancient history, fossils.

As far as she was concerned I was pitching a film about paleontology.

Sometime later, dodging puddles as I walked out to my car, I reflected on how much easier stories sometimes developed in Old Hollywood, before the studios were industrial conglomerates, before the caffeine-addled producers were business school bean counters and computer programmers. In those days every major studio was turning out fifty or more feature films a year and every producer was desperate for a script. This made guys like Robert Hopkins indispensable. Hoppie was legendary around the MGM studio for his story pitches. He didn't write pictures, they said, he talked them. As the tale is told, half-dozen Metro producers were standing in the hall one day wringing their hands. They needed a story for Clark Gable and they needed one in a hurry. Gable was MGM's big male star, sure-fire box office, and they needed to keep him busy to keep the money rolling in. So Hoppie overhears the conversation. Clutching his ever-present cup of coffee, he shuffles up to the group and says: “Two guys in San Francisco. One's a priest, the other guy runs a big saloon, and you end it with the San Francisco earthquake - bang.” Hoppie gives one of the suits an elbow in the ribs - “Do I have to tell you more?” - and keeps walking. The film `San Francisco' was released eight months later, in June, 1936. Gable played the saloon keeper, Spencer Tracy was the priest. Janette McDonald played Gable's love interest. It won one Oscar, was nominated for five more, and made a lot of money for MGM.

As for `The Third Act', stay tuned. It's a long story. To almost quote Bette Davis's famous line from `All About Eve': “Fasten your seat belts, it's going to be a bumpy ride.”